TLC Rocket Fuel

Strategies & Inclusions

Teach with confidence knowing your instructional resources and student materials are informed by science.

The Literacy Big 6

The concept of the Literacy Big 6 emerged from extensive research on reading instruction and literacy development, particularly influenced by the findings of the National Reading Panel (NRP) in the United States.

National Reading Panel (NRP) Report - USA

In 1997, the U.S. Congress convened the National Reading Panel to assess the effectiveness of various approaches to teaching children to read. The panel reviewed over 100,000 studies on reading instruction conducted since 1966, focusing on evidence-based practices. The NRP published its report in 2000, identifying five critical components of effective reading instruction, which later became known as the Literacy Big 5.

The inclusion of oral language as a sixth component was influenced by a growing body of research that highlighted its critical importance in early literacy development. While the original Literacy Big 5 (phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension) provided a robust framework for literacy instruction, educators and researchers noticed that oral language skills were foundational and interwoven with these components.

National Inquiry into the Teaching of Literacy (NITL) - Australia

In 2005, the Australian Government published the results of the National Inquiry into the Teaching of Literacy, often referred to as the ‘Rowe Report.’ The inquiry, led by Dr Ken Rowe, examined literacy teaching practices and confirmed the importance of the Literacy Big 5 components.

Rose Review - UK

In 2006, the UK conducted the Independent Review of the Teaching of Early Reading, led by Sir Jim Rose. The Rose Review echoed the findings of the NRP and emphasised the importance of systematic phonics instruction.

The Research Base

The Literacy Big 6 framework is supported by a vast body of research from cognitive psychology, education, and linguistics. Key research findings include:

Oral Language

Oral language lays the foundation for reading and writing, influencing academic success throughout schooling (Snow et al., 1995; Wise et al, 2007). Children immersed in rich, complex conversations develop strong vocabularies, grammatical skills and phonological awareness, which are essential for understanding and interpreting texts. Effective teaching of oral language is crucial at all educational levels, as strong oral skills underpin expressive and receptive communication. Research highlights the importance of language role models—students benefit from interacting with proficient language users to expand vocabulary and language structures. Teachers enhance oral language development through dialogic practices, modeling complex syntax and encouraging interactive exchanges. Additionally, reading quality texts and engaging students in analytic discussions introduces new vocabulary and complex syntax. To implement these strategies effectively, teachers must understand the connection between oral language development and reading success.

Experiences with books, print, and observing reading and writing activities help children grasp the concept that symbols on a page represent language, how books function, and basic literacy conventions. Reading stories to children and pointing out words fosters understanding of how spoken language transforms into written language. However, children from language- and print-poor environments face disadvantages, making it crucial for schools to provide a stimulating and supportive literacy environment.

Phonemic Awareness

Phonological awareness involves recognising the sounds of speech, including breaking speech into words, syllables, and phonemes. Phonemic awareness, the ability to identify individual sounds, is the most critical component for reading development. It predicts future reading ability better than socioeconomic status or IQ (Adams, 1990; Bowey, 2005; Ehri et al, 2001, Snow et al, 1998; Stanovich & Stanovich, 2003). Key phonemic skills for reading and spelling are blending and segmenting phonemes. Developing these skills in a child’s foundational years at school is essential for their literacy success.

Phonics

Children must learn the relationship between sounds and letters (the alphabetic principle or phonics), to decode words and read effectively. Understanding sound-letter mapping is essential for reading an alphabetic language like English. Empirical evidence supports a synthetic phonics approach for beginning and struggling readers. (National Reading Panel, 2000; Rose, 2006; Rowe, 2005). This method involves teaching single letters and common letter combinations systematically, explicitly, and in a sequence that enables blending (synthesizing) sounds into words, starting from the first weeks of formal schooling. This foundational skill is critical for developing strong reading abilities.

Vocabulary

Vocabulary is essential for reading comprehension, as knowing word meanings helps children decode and make sense of sentences. While children from literate, language-rich environments develop vocabulary naturally through exposure to conversations, stories and media, others from less advantaged backgrounds face limited vocabulary growth which in turn impacts reading skills acquisition. Indirect vocabulary learning alone cannot bridge this gap; direct instruction is effective in building vocabulary for all children, especially those with limited exposure. (Beck & McKeown, 2007; Tomeson & Aarnoutse, 1998). Developing a broad, versatile vocabulary, requires deliberate, robust instruction and meaningful practice (Beck & McKeown, 2002) to foster deep understanding and word consciousness in preparation for secondary school challenges.

Vocabulary knowledge, closely tied to oral language development, is crucial for reading comprehension. A rich vocabulary enables accurate reading and correlates with later academic success when encountering complex texts. Deep vocabulary knowledge includes understanding word associations, flexible usage in various contexts, and how context shapes meanings (Beck et al., 2013; Biemiller, 1999; Graves, 2006).

Morphological knowledge, the study of morphemes (smallest meaningful language units), supports vocabulary and influences the development of oral language, spelling, reading, and comprehension (Apel, 2014; Bowers et al., 2010; Goodwin & Ahn, 2013).

Explicit teaching of morphology, such as understanding prefixes, roots, and suffixes, helps students grasp and manipulate meaning effectively.

Fluency

Fluency is the ability to read connected text rapidly, smoothly, effortlessly and automatically, with little conscious attention to the mechanics of reading, such as decoding (Singelton, 2009, p.47). Developing fluency allows students to focus on comprehension, enriching their reading experience. Fluency relies on three key components: accuracy, speed, and prosody.

Accuracy ensures words are read correctly, while speed measures how quickly they are read, typically assessed by Oral Reading Fluency (ORF). Prosody—expression, intonation, and phrasing—enhances meaning and comprehension. It involves reading rate, phrasing, and intonation, all reflecting comprehension. Fluency and comprehension are interdependent; poor fluency hinders comprehension, while lack of understanding affects phrasing.

Research has shown reading fluency improves when students receive a model of fluent reading with performance feedback and practice with texts at their independent reading level (Stevens et al., 2017, p. 576). Setting a performance goal and engaging in repeated reading, especially four or more times, significantly enhances fluency compared to fewer repetitions (Suggate, 2016). This repetition builds automaticity, relying on memory retrieval rather than adjustments to other reading skills.

Comprehension

Comprehension is the ultimate goal of reading, requiring more than decoding skills. It depends on vocabulary knowledge, background understanding, familiarity with text structures, and verbal reasoning to infer meaning. Proficient readers employ strategies such as understanding the purpose of their reading, recognizing the author’s intent, monitoring comprehension, and adjusting strategies as needed (Konza, SA-DECS, 2011). These skills help readers draw meaning, identify key information, and make connections. Research shows that background knowledge can impact comprehension despite the skill level of the reader. The more knowledge a reader brings to a text, the more able they are in comprehending a text (Smith et al., 2021).

Explicit teaching improves reading comprehension by developing key skills like word reading and language comprehension (Catts, 2018; National Reading Panel, 2000). Explicit teaching of background knowledge, enhances engagement and motivation (Duke & Cartwright, 2021). Teaching text structures also aids comprehension by helping readers identify and focus on key details in a text (Hogan et al., 2011).

Overall, the evidence suggests that the most effective interventions for improving reading comprehension focus on building background knowledge and addressing the key constructs of the science of reading (Apel et al., 2012; Duke & Cartwright, 2021; Foorman et al., 2018; Smith et al., 2021).

Highly Recommended Reading:

Unpacking the science of reading research

Rollo, G., & Picker, K. (2024). Unpacking the science of reading research. Australian Council for Educational Research.

View all referencesReferences

Adams, M. J. (1990). Beginning to read: Thinking and learning about print. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

Beck, I., McKeown, M.G., & Kucan, L. (2002). Bringing words to life: Robust vocabulary instruction. New York: Guilford Press

Beck, I., & McKeown, M.G. (2007). Increasing young low income children’s oral vocabulary repertoires through rich and focused instruction. Elementary School Journal, 107(3), 251–271.

Bowey, J.A. (2005). Predicting individual differences in learning to read. In M. Snowling & C. Hulme (Eds.), The science of reading: A handbook (pp.155–172). Oxford: Blackwell.

Apel, K. (2014). A comprehensive definition of morphological awareness: Implications for assessment. Topics in Language Disorders, 34(3), 197–209. https://doi.org/10.1097 TLD.0000000000000019

Catts, H. W. (2018). The simple view of reading: Advancements and false impressions. Remedial and Special Education, 39(5), 317–323. https://doi. org/10.1177/0741932518767563

Duke, N. K., & Cartwright, K. B. (2021).

The science of reading progresses: Communicating advances beyond the Simple View of Reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(S1). https://doi.org/10.1002/ rrq.411

Ehri, L.C., Nunes, S., & Willows, D.M., Schuster, B., Yaghoub-Zadeh, Z., & Shanahan, T. (2001). Phonemic awareness instruction helps children learn to read: Evidence from the National Reading Panel’s meta-analysis. Reading Research Quarterly, 36(3), 250–87.

Foorman, B. R., Petscher, Y., & Herrera, S. (2018). Unique and common effects of decoding and language factors in predicting reading comprehension in grades 1–10. Learning and Individual Differences, 63, 12–23. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2018.02.011

Hogan, T., Bridges, M., Justice, L., & Cain, K. (2011). Increasing higher level language skills to improve reading comprehension. Focus on Exceptional Children, 44(3), 1–20.

Konza, D. (2011). Fluency (Research into Practice). Government of South Australia, Department of Education and Children’s Services. https://www.ecu.edu.au/__data/ assets/pdf_file/0005/663701/SA-DECS- Fluency-doc.pdf

National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read. An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/sites/default/ files/publications/pubs/nrp/Documents/ report. pdf

Rose, J. (2006). Independent Review of the Teaching of Early Reading: Final report. Department for Education and Skills. https:// dera.ioe.ac.uk/id/eprint/5551/2/report.pdf

Rowe, K. (2005). Teaching reading: Report and recommendations. Department of Education, Science and Training. https://research.acer. edu.au/tll_misc/5

Singelton, C. (2009). Intervention for dyslexia: A review of published evidence on the impact of specialist dyslexia teaching. Commissioned by the Steering Committee for the “No to Failure” project and funded by the Department for Children, Schools and Families, United Kingdom.

Smith, R., Snow, P., Serry, T., & Hammond, L. (2021). The role of background knowledge in reading comprehension: A critical review. Reading Psychology, 42(3), 214–240. https:// doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2021.1888348

Snow, C.E., Burns, M.S., & Griffin, P. (1998). Preventing reading difficulties in young children. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Stanovich, P.J., & Stanovich, K.E. (2003). Using research and reason in education: How teachers can use scientifically based research to make curricular and instructional decisions. Washington DC: US Department of Education. Available from http://www.nifl.gov/partnershipforreading/publications/html/ stanovich/ Thurston, L.L. (1946). A note on a re-analysis of Da

Stevens, E. A., Walker, M. A., & Vaughn, S. (2017). The effects of reading fluency interventions on the reading fluency and reading comprehension performance

of elementary students with learning disabilities: A synthesis of the research from 2001 to 2014. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 50(5), 576–590. https://doi.org/10.1177/002219416638028

Suggate, S. P. (2016). A meta-analysis of the long-term effects of phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, and reading comprehension interventions. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 49(1), 77–96. https:// doi.org/10.1177/0022219414528540

Tomeson, M. & Aarnoutse, C. (1998). Effects of an instructional programme for deriving word meaning. Educational Studies, 24(1), 107–222.

Wise, J.C., Sevcik, R.A., Morris, R.D., Lovett, M.W., & Wolf, M (2007). The relationship among receptive and expressive vocabulary, listening comprehension, pre-reading skills, word identification skills and reading comprehension by children with reading disabilities. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 50(4), 1093–1109.

Scarborough’s Reading Rope

Scarborough’s Reading Rope is a metaphorical model developed by Hollis Scarborough in the late 1990s to illustrate the complexity of reading. It represents the various strands of skills and knowledge that are necessary for proficient reading.

The strands include language comprehension (both listening and reading), decoding (phonological awareness and decoding skills), and fluency (automaticity and prosody).

These strands intertwine to form a rope, representing the interconnected nature of reading. Scarborough’s Reading Rope has stood the test of time because it provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the multifaceted nature of reading development, guiding educators in designing effective instruction and interventions tailored to individual students’ needs.

Additionally, its flexibility allows for integration with emerging research and evolving educational practices, ensuring its continued relevance in literacy education.

TLC structured literacy program includes instruction in both sides of the Reading Rope, ensuring that children’s literacy learning incorporates the crucial skills of building background and vocabulary knowledge along with knowledge around language and text structures. When these areas of knowledge develop alongside ‘bottom of the rope’ foundational word recognition skills, the desired outcome of reading comprehension will be achieved.

Systematic Synthetic Phonics

TLC utilises a systematic, synthetic phonics approach to teach reading and spelling that focuses on the systematic and explicit instruction of letter-sound relationships. TLC is a linguistic phonics programme, meaning it has a speech to print orientation. This involves breaking down words into their individual phonemes (sounds) and teaching students the corresponding graphemes (letters or letter combinations) that represent those sounds.

When children bring their explicitly taught knowledge of phonological awareness, print concepts and the alphabetic code to the task of decoding a word, they ascribe meaning (with or without help) to that word and it is stored in the brain for automatic retrieval. This process, by which every word eventually becomes a ‘sight word’, is called orthographic mapping.

Spelling generalisations are introduced early on to assist children in their spelling choices. As students progress to multi-syllabic words, explicit instruction assists students in using their knowledge around syllables, morphology and decoding to orthographically map and decode more complex words.

The 40+ English phonemes are the basis for the code and never change. These 40+ sounds provide a pivot point around which the code can reverse. The 40+ sounds will always play fair even if our spelling system does not.

Dianne McGuiness

TLC Evidence-Informed Word Recognition Program Inclusions

Systematic Instruction

TLC utilises a systematic, structured, linguistic approach to teaching reading and writing, starting with basic sound/letter correspondences and gradually progressing to more complex phonics patterns.

Explicit Instruction

High quality, Tier 1 and Tier 2 instructional materials are provided to assist teachers in explicitly teaching the crucial foundational decoding and encoding skills. Teaching PowerPoints provide clear explanations, direct instruction and opportunities for student engagement and interaction.

Phonemic Awareness

Activities that help students develop phonemic awareness, the ability to hear, identify and manipulate individual phonemes in spoken words, are included in the TLC Word Recognition program component. To align with current best practice, letters are added to almost all of the phonemic awareness activities from the get-go.

Phonics Instruction

TLC follows a research-informed scope and sequence for phonics instruction which involves teaching the relationships between phonemes and graphemes, starting with most common and progressing to less common correspondences.

Decodable Texts

The program includes a collection of sound/letter focus decodable texts that contain words with the phonics patterns students have learned, allowing them to apply their decoding skills in reading. TLC recommends the use of decodable readers in the very early stages of reading.

Multisensory Techniques

TLC incorporates multisensory activities that engage visual, auditory, and kinesthetic modalities to enhance learning and retention of explicilty taught phonics concepts.

Structured Practice

Guided practice, word-work lessons provide ongoing, structured practice opportunities to apply phonics skills in decoding and encoding activities including orthographic mapping, syllable work, and sentence construction.

Progress Monitoring

Embedded into the TLC program are progress monitoring assessments and tools to regularly identify areas of strength and weakness so teachers can adjust Tier 1 instruction and Tier 2 interventions to meet students’ needs.

Integration with Other Language Skills

TLC integrates phonics instruction with other language skills such as vocabulary development and writing skills.

This structured approach to teaching foundational word recognition skills streamlines literacy instruction by providing a logical pathway for children to develop the pre-requisite skills for comprehending written text.

Various studies researching the effectiveness of linguistic phonics programs include:

- Lippincott Program (Bond and Dykstra, 1967)

- Dockland’s Study (Stuart, 1999)

- Clackmannanshire Study (Watson and Johnson 2004)

- Queen’s University Belfast Study (Gray et. Al, 2007)

eCode

The International Phonetic Alphabet standardises the representation of speech sounds across all languages, eliminating ambiguity and variation in transcription. For linguists it serves as a critical tool in analysing, comparing and preserving phonetic aspects of languages worldwide. We ask young children, budding linguists, to become proficient in identifying, manipulating and mapping sounds to letters without the benefit of a complete and transparent alphabetic code that represents all 44 speech sounds of the English language.

Unique to TLC is an artificial, transparent, 'emoji code' (eCode), consisting of easily identifiable visual prompts for all 44 speech sounds. eCode provides a ‘stable sound hook’ to hang the various spelling patterns on. When children hear the sound, they start to use their developing spelling knowledge to choose the correct spelling for a word. Although a systematic, synthetic, scope and sequence is followed, eCode gives children access to the complete code and various spelling choices from the get-go, accelerating both decoding and encoding skills. eCode is used initially as a visual prompt to explicitly teach and cement the phoneme/grapheme correspondences. It is also highly effective for introducing children to above-level phoneme/grapheme correspondences or less common spelling patterns prior to explicit teaching, for example, in the teaching of irregular, high frequency words.

Structured Literacy Sequence

TLC emphasizes clear and systematic instruction across all essential literacy components. The vital role of oral language abilities in literacy development underscores TLC structured literacy instruction.

TLC Structured Literacy

TLC emphasizes clear and systematic instruction across all essential literacy components. This includes foundational skills like decoding and spelling, along with advanced skills such as reading comprehension and written expression. The vital role of oral language abilities in literacy development underscores structured literacy instruction.

Elements & Teaching Methods

TLC Structured Literacy infographic is a visual representation used to illustrate the elements and teaching methods incorporated in TLC’s comprehensive program. This integrated approach to teaching structured literacy ensures each element is supportive of and in service to all of the other components.

Element

Phonology (Foundation to Gr 2)

Phonics & Spelling (Foundation to Gr 2)

Syllables (Gr 1 & Gr 2)

Morphology (Foundation to Gr 2)

Syntax (Foundation to Gr 2)

Semantics (Foundation to Gr 2) Text Comprehension

Written Expression (Foundation to Gr 2)

Building Background Knowledge & Vocabulary Knowledge (Foundation to Gr 2)

What is it?

- Understanding and working with sounds in spoken language

- Includes phonemic awareness, which is the ability to identify and manipulate individual phonemes in words

- Understanding the relationship between phonemes and their corresponding graphemes

- Includes phonics instruction

- Includes both decoding and encoding instruction

- Understanding the different types of syllables and the rules for dividing words into syllables

- Helps with decoding and encoding longer words

- Understanding the meaning and structure of words, including prefixes, suffixes, roots, and base words

- Helps students understand how words are formed and how they can be modified

- Understanding the set of principles that dictate the structure of sentences

- Includes understanding grammar rules and the function of different parts of speech within a sentence

- Understanding how words are organized in oral and written language

- Helps students understand the meaning of text

- Written expression is a highly complex, cognitive process, resulting in text generation at word, sentence and text level

- Oral expression and writing mechanics are important factors in developing written expression

- Building background knowledge and vocabulary knowledge around a text topic provides the necessary context and tools for understanding, interpreting, and engaging with the text

- Helps students in comprehending texts and composing oral and written responses to text

TLC Inclusions

- 3 Week Intensive Phonological Awareness Unit - Vocal Productions (Foundation)

- Phonemic Awareness Drills

- Phoneme manipulation (with letters) practice and monitoring

- Systematic synthetic sequence of phoneme/grapheme correspondences

- Sound walls

- Phonemic Awareness Skills (with letters)

- Orthographic Mapping

- Encoding/Decoding taught simultaneously

- The rules and patterns of spelling, as well as the exceptions

- High Frequency Word instruction partially aligned to phonics scope and sequence

- Decodable text kits

- Syllable type instruction aligned to phonics scope and sequence

- Teach and practise syllable patterns and division rules (Predominantly Yr 2)

- Morphology instruction aligned to phonics scope and sequence

- Integrate morphology instruction with vocabulary instruction in written and oral language

- Instruction follows a carefully planned sequence

- Sentence scrambles, dictation, grammar, sentence building and parts of speech - taught in the context of themed writing tasks

- Intensive instruction and practice in sentence composition - oral and written

- Understanding how words are organized in oral and written language

- Helps students understand the meaning of text

- Comprehension of oral and written language is developed by teaching word meanings, interpretation of phrases and sentences, text structures and verbal reasoning skills

- Includes developing background knowledge, vocabulary instruction, text organisation and effective comprehension strategies

- Includes instruction in higher order writing components: planning, drafting, reviewing and revising, starting at sentence level and progressing to longer compositions in various genres

- Includes instruction in lower-level transcription skills, (handwriting and spelling) to complement the higher order writing skills

Teaching Methods

TLC Structured Literacy infographic emphasizes research-informed teaching methods. These instructional approaches are particularly effective for students with reading difficulties, ensuring that all necessary skills are taught explicitly, reinforced cumulatively, organized sequentially, informed by data, delivered through multiple modalities, and supported through scaffolding.

- Explicit instruction involves direct teaching of concepts, with clear and specific explanations, modelling, and guided practice.

- Cumulative instruction builds upon previously learned skills, continuously reinforcing and integrating new knowledge with old.

- Sequential instruction follows a logical order, progressing from simpler to more complex skills.

- Data-Driven instruction involves using progress monitoring assessment data to inform Tier 1 instructional tweaks and Tier 2 and 3 interventions.

- Multi-Modal instruction uses various teaching methods and sensory modalities (visual, auditory, kinesthetic) to engage students.

- Scaffolded instruction provides temporary support to students as they learn new skills, gradually removing the support as students become more proficient.

High Impact Teaching Strategies

TLC has embedded tried and tested instructional methods, proven to be highly effective in improving learner achievement.

TLC High Impact Teaching Strategies

High Impact Teaching Strategies are tried and tested instructional methods that are highly effective in improving learner achievement. Researcher, John Hattie, has conducted extensive meta analyses to identify, summarise, and rank the most effective instructional approaches for improving student understanding. We’ve distilled some of these findings into quality teaching instructional practice and student learning activities in the TLC programme.

We’ve done the research for you, now you can focus on delivering top notch Tier 1 instruction.

The greatest influence on student progression in learning is having highly expert, inspired and passionate teachers and school leaders working together to maximise the effect of teaching on all students in their care.

John Hattie

Progress Monitoring &

Response to Intervention

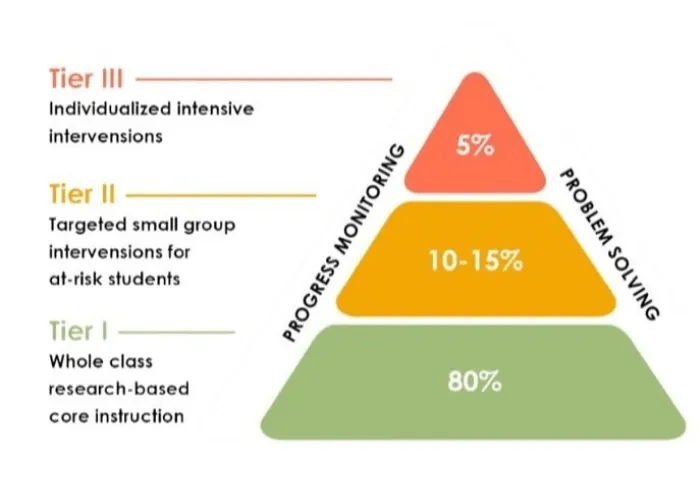

The Response to Intervention (RTI) framework is a multi-tiered approach used in education to identify and support students with learning difficulties.

Response to Intervention

We encourage all teachers to introduce an RTI framework in their classrooms. The TLC program has word recognition assessments (6-8 weeks) and sound practice cards (weekly) embedded to provide teachers with the progress monitoring tools to inform instructional tweaks and Tier 2 and 3 interventions. We also recommend the use of universal screeners three times a year.

The Response to Intervention (RTI) framework is a multi-tiered approach used in education to identify and support students with learning difficulties. Research on RTI emphasises early intervention and ongoing monitoring to provide timely support to struggling students. The framework typically involves three tiers: Tier 1 provides high-quality instruction to all students, Tier 2 offers targeted interventions to those who need additional support, and Tier 3 provides intensive interventions for students who require more specialised assistance.

Studies have shown that RTI can effectively identify and support students with learning disabilities, improve academic outcomes, and reduce the need for special education referrals.

Additionally, RTI has been found to be beneficial in promoting collaboration among educators, fostering a data-driven decision-making process, and promoting a culture of continuous improvement in schools. Overall, research supports the effectiveness of RTI in meeting the diverse learning needs of students and promoting their academic success.

Tier 2 interventions are best delivered through small-group instruction using strategies that directly target a skill deficit. Research has shown that small- group instruction can be highly effective in helping students master essential learnings (D’Agostino & Murphy, 2004; Vaughn, Gersten, & Chard, 2000). The TLC literacy rotations have been set up to facilitate small group, differentiated learning and Tier 2 interventions. Numerous resources and tools are included in the TLC program to assist with Tier 2 and Tier 3 interventions.

The end of the RTI process is not Special Education; it’s when the student’s problem is solved.

Sir Jim Rose

The Science of Learning

The Science of Learning can be defined as the body of research from cognitive science that explains how we learn. Learning how to best utilize this research in TLC instructional resources is an on-going pursuit, driven by teacher feedback and student data.

The Science of Learning

TLC is committed to continual learning around this crucial body of work and embedding these cognitive principles in the program. Our goal is to ensure educators are connected to the best providers of the research around the Science of Learning.

The following core set of focus principles have been researched and collated by the organisation Deans for Impact. We highly recommend teachers access their resources at https://www.deansforimpact.org.

The Response to Intervention (RTI) framework is a multi-tiered approach used in education to identify and support students with learning difficulties. Research on RTI emphasises early intervention and ongoing monitoring to provide timely support to struggling students. The framework typically involves three tiers: Tier 1 provides high-quality instruction to all students, Tier 2 offers targeted interventions to those who need additional support, and Tier 3 provides intensive interventions for students who require more specialised assistance.

Science of Learning - Focus Principles

- Building on Prior Knowledge: Learning is more effective when new ideas are connected to what students already know. Teachers should assess prior knowledge and design curriculum carefully to facilitate meaningful connections and higher-order thinking.

- Avoid Cognitive Overload: Working memory is limited, and too much information at once can hinder learning. Teachers should scaffold and adjust tasks to account for individual differences in students’ prior knowledge.

- Focus on Meaning: Surface learning (memorizing facts) is necessary before progressing to deeper learning levels, where students analyze and engage with ideas. Teachers must create opportunities for deeper learning and highlight the relevance of what students are learning.

- Practise with Purpose: Effective practice should push students out of their comfort zones, have clear goals, require focus, incorporate feedback, and develop expertise through mental models.

- Build Feedback Loops: High-quality feedback is timely, specific, and actionable. Students need opportunities to use feedback to improve their skills and understanding.

- Create a Motivating Environment: A sense of belonging and emotional safety is critical for learning. While motivation and engagement are necessary, they must be paired with rigorous learning opportunities for optimal outcomes.

Knowledge Building, Comprehension & Writing

The TLC program uses the Know, Grow, Go learning framework to assess what children know or need to know to access the learning. Explicit instruction is provided to grow their knowledge and then opportunities are provided for students to apply that knowledge.

Knowledge Building Framework

Children come to school with varying degrees of background knowledge and vocabulary knowledge. Building a child’s knowledge about the world expands their ability to access a wide range of texts, materials and resources. Students with limited vocabulary or background knowledge may struggle to comprehend complex texts or engage meaningfully with academic content, placing them at a disadvantage compared to their peers.

Ensuring that all students have access to opportunities for knowledge building and vocabulary development around various topics and language/text structures is essential for promoting educational equity and levelling the playing field for students from diverse backgrounds.

The TLC program uses the Know, Grow, Go learning framework to assess what children know or need to know to access the learning. Read-alouds and secondary sources of information are used to grow their knowledge around a topic before they are asked to go and use their newly acquired knowledge to complete an oral or written language task.

TLC uses connected text sets, themed around an overarching ‘Big Idea’ to scaffold the learning required to build networks of knowledge.

What you’re helping children do is create a mosaic; putting all those ideas together in a knowledge network. If you don’t do it explicitly, many children cannot do it on their own.

Susan B Newman

In the act of writing, students also form new relationships among ideas. Writing helps students integrate their thoughts.

Joan Sedita

‘Talk to Write’ & ‘Write to Text’ Structured Writing Instruction

TLC writing instruction draws on the evidence-based instructional approaches from three writing framework handbooks.

Joan Sedita’s book, The Writing Rope, is a comprehensive framework that defines the interconnected components and processes necessary for proficient writing skills development. Similar to the Scarborough’s Reading Rope for reading, The Writing Rope represents the multiple strands of skills and knowledge that contribute to effective writing. These strands include foundational skills such as handwriting, spelling and punctuation, as well as higher-level skills like vocabulary, sentence construction and organisation.

TLC also draws on the work of Judith Hochman and Natalie Wexler (The Writing Revolution) which emphasises the importance of integrating content-rich instruction, explicit sentence construction skill development, structured writing processes, meaningful practice and exposure to high-quality texts to promote students’ writing proficiency and critical thinking abilities.

We also recommend teachers become familiar with Pie Corbett’s and Julia Strong’s book, Talk for Writing Across the Curriculum, in which oral language development (discussion, storytelling, and collaborative activities.) is prioritised as a pre-requisite for writing. The approach also incorporates grammar instruction and vocabulary development within the context of meaningful writing tasks.

TLC writing lessons provide a scaffolded framework to develop students’ writing skills, confidence, and love for writing.

Sentence-level work is the engine that will propel your students from writing the way they speak to using the structures of written language.

Judith Hochman